And so yesterday we walked through a warm and busy London to the South Bank, where, after sharing a doughy cheese

pierogi off the real food street market, we ascended bloodstained concrete stairs to the Hayward Gallery.

The exhibition is entitled "

Invisible: Art about the Unseen, 1957 -2012". We paid, were given tickets after reminding the counter clerk (was this a foretaste of the installation?) and gave them to the attendant at the door, who said something we didn't catch, so we asked him to repeat it. It was "Can you see me?" with what I suppose he hoped was an appropriately ironic smirk; I guess we should have replied, "Yes, but we can't hear you."

In we went, noting an

avertissement that warned visitors that some might have difficulty reading the labels. Which were printed in white, on transparent plastic sheets, against white walls. Not that there were that many exhibits; now call me middle-browed, but if I'm offered nothing I want a lot of it for my money. In keeping, the gallery was sparsely attended, though one woman was making up for it by gazing very intensely at an empty section of wall. My wife speculates that she might have lost her glasses and thought she was looking at something. Or perhaps she was merely entering into the spirit of the thing (or the nothing).

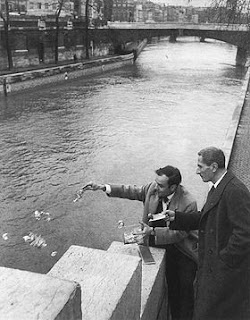

The first item I inspected with any care was a press cutting from 1959, about Yves Klein's stunt "

Zone de Sensibilité Picturale Immatérielle." Klein sold tickets in exchange for shreds of gold leaf (20 grams for the first exhibition - rising later to 80 grams, such are the effects of inflation). If the buyer opted to convert these into an immaterial experience, he burned his ticket (at least he got one first time of asking, I assume) and the artist threw half the gold into the river Seine; otherwise Klein kept the lot. So the artist got something tangible and conventionally valuable, whatever happened. Gallic cunning? But it's possible, of course, that I may be doing Klein an injustice, for

in 1980 one of his pieces was discovered quite by accident in an Italian convent, having been anonymously deposited there in 1961 as a votive offering by the artist, who prayed for success and the increasing beauty of his works.

I do suspect that French philosophy is basically for impressing French chicks. It worked with Simone de Beauvoir, for one; and years ago in Paris, my beloved and I were watching TV and caught an interview with Serge Gainsbourg (conducted by Jane Birkin, as I recall) where he was acting the literary lion

à la française - unshaven, Gauloised, possibly well-oiled as we used to say, and spouting

un grand tas de testicules about

la vie,

l'amour etc. Fortunately we were well-oiled too, and understood him as drunks do each other. French women know that their role is to serve the gorgeous peacock; one remembers H E Bates' "A Breath of French Air", where muscular Adonises play ball on the beach, admired by mousy-looking girls with what the Irish call

streely hair.

Maybe, as with

Sartre in 1943, the concept of nothingness (or for others, the numinous) is a reaction to a time when you were supposed to join one team or the other, with no standing on the sidelines (it's getting like that again now, I sense).

À bas les salauds, and all that; spit in the eye of those "

assured of certain certainties"; let the spirit off the leash of Reason.

Having said that, Sartre seems to have been able to redirect his gaze to concrete matters when it suited him, as witness

the controversy over his stepping into a Jewish professor's job when it became forcibly vacant under the Nazis; and in the 1968 Paris student riots, he suddenly abandoned his fundamental stance on existentialism and became able to believe in

collective freedom, at least for a while. Perhaps his

volte-face and surrender to the authority of Marxism is the core of surreal rebellion. As a paper

already cited says,

"Hysterical questioning is critical of power (“Why have you done this? This is not just!”), but beneath it all is a provocation to the father figure to appear and to interpellate more successfully."

Back to the matter in hand. There was other stuff here, including Robert Barry's Energy Field (AM 130 KHz) from 1968 (a wooden box with a battery and coil), and a room with a couple of air coolers (my wife said she found these things very welcome after a sauna). One room was a blackout (pictured below; fortunately I captured another visitor, so I got both ground and figure, the essentials of all Western art).

Then there was a wide upper gallery. This space spoke to me: it said, 'You paid fourteen quid for this." And finally, something for the kids: Jeppe Hein's Invisible Labyrinth. You know, like those inlaid floor mazes found in some theme parks and gardens, only here you had to memorise the routes.

Good art (like radio plays) makes you do some of the work, and there's no shortage of clever people stropping their intellects on this one:

Of course, reviewers don't pay to get in, and on the whole, nor would we have, if we'd known what was in store. But surely every show must have a closing number, and to play you out here's the orchestral version of John Cage's 4' 33'' so you can have something to hum as you leave:

Coincidentally, the show we saw after, "

Yes, Prime Minister" at the Trafalgar Studios (Whitehall Theatre as was), also featured a nothing, this time the Prime Minister, described in the play as "a vacuum". It was funny and beautifully acted, but edgier and darker than the old TV programmes - as with Stravinsky's

The Rite Of Spring, we scent

in the artist's work

a storm coming to us in real life.

A shame then that five minutes down the road from there we have a PM who is the human equivalent of a German beach towel, merely keeping the place for a real person to come later. Like Jim Hacker,

we now see Cam thrashing about with a handful of Blairite eye-catching initiatives to divert attention from his failure to achieve anything*. As we passed the now-gated entrance to Downing Street I said, make the most of it, you've got twelve months.